Jose Storopoli, PhD

Fullstack and Progressive Web Apps in Rust: A Tale of a Sudoku Spyware

It all started when I had to accompany my mom to the hospital. It was just a routine checkup, but I had to wait for a few hours. I brought my laptop with me, since they have good WiFi and I could work on my projects. Then I realized that my mom was playing a Sudoku game on her phone. I couln’t help but notice that the game was full of ads and it was asking for a lot of permissions, like location and sensor data. So I decided to make a Sudoku game for her, without ads or using any permission. It wouldn’t even need to ask for the blessing of Google or Tim Apple since it was a Progressive Web App (PWA) and it would work offline.

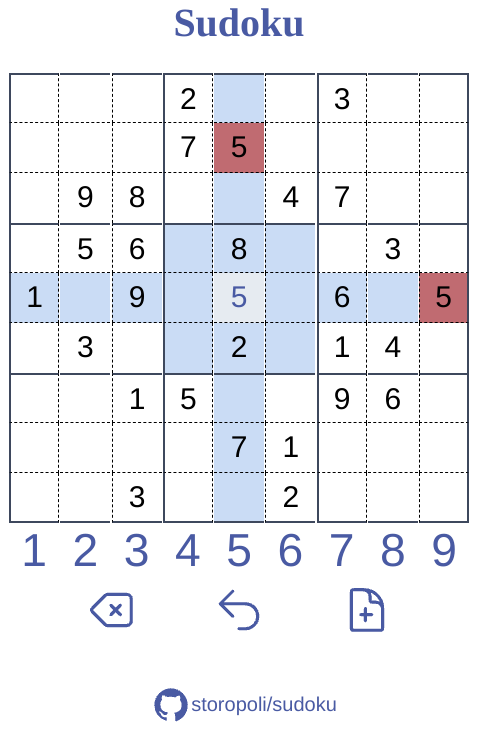

You can play the game at storopoli.io/sudoku or check the source code at storopoli/sudoku.

Here’s a screenshot of the game:

Tools of Choice

So what would I use to build this game? Only one thing: Dioxus. Dioxus is a fullstack framework for Rust, that allows you to build web applications with Rust. You can benefit from the safety and performance of Rust, powerful type system and borrow checker, along with the low memory footprint.

That’s it. Just Rust and HTML with some raw CSS. No “YavaScript”. No Node.js. No npm. No webpack. No Tailwind CSS. Just cargo run --release and you’re done.

Package Management

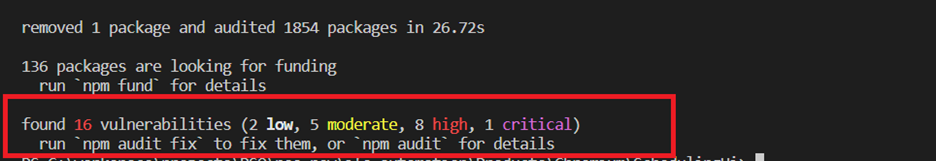

Using Rust for fullstack development is an amazing thing. First, package management is a breeze with Cargo. Second, you don’t have to worry about “npm vulnerabilities”. Have you ever gone into your project and ran npm audit?

This is solvable with Rust.

Runtime Errors

An additional advantage is that you don’t have to worry about common runtime errors like undefined is not a function or null is not an object. These are all picked-up by Rust on compile time. So you can focus on the logic of your application knowing that it will work as expected.

A common workflow in Rust fullstack applications is to use Rust’s powerful type system to parse any user input into a type that you can trust, and then propagate that type throughout your application. This way you can be sure that you’re not going to have any runtime errors due to invalid input. This is not the case with “YavaScript”. You need to validate the input at every step of the way, and you can’t be sure that the input is valid at any point in time.

You can sleep soundly at night knowing that your application won’t crash and as long as the host machine has electricity and internet access, your app is working as expected.

Performance

Rust is known for its performance. This is due to the fact that Rust gives you control over deciding on which type you’ll use for a variable. This is not the case with “YavaScript”, where you can’t decide if a variable is a number or a string. Also you can use references and lifetimes to avoid copying data around.

So, if you make sane decisions, like u8 (unsigned 8-bit integer) instead of i32 (signed 32-bit integer) for a number that will never be greater than 255, you can have a very low memory footprint. Also you can use &str (string slice) instead of String to avoid copying strings around.

You just don’t have this level of control with “YavaScript”. You get either strings or numbers and you can’t decide on the size of the number. And all of your strings will be heap-allocated and copied around.

Progressive Web Apps

Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) are web applications that are regular web pages or websites, but can appear to the user like traditional applications or native mobile applications. Since they use the device’s browser, they don’t need to be installed through an app store. This is a great advantage, since you don’t have to ask for permissions to Google or Tim Apple.

In Dioxus making a PWA was really easy. There is a PWA template in the examples/ directory in their repository. You just have to follow the instructions in the README and you’re done. In my case, I only had to change the metadata in the manifest.json file and add what I wanted to cache in the service worker .js file. These were only the favicon icon and the CSS style file.

Sudoku Algorithm

I didn’t have to worry about the algorithm to generate the Sudoku board. This was already implemented in the sudoku crate. But I had to implement some Sudoku logic to make the user interface work.

Some things that I had to implement were:

- find the related cells. Given a cell, find the cells in the same row, column and sub-grid.

- find the conflicting cells. Given a cell, find the cells in the same row, column and sub-grid that have the same value.

Find the Conflicting Cells

To find the conflicting cells, you need to get the value of the target cell. Then you can get the related cells and filter the ones that have the same value as the target cell. Easy peasy.

Here’s the code:

pub fn get_conflicting_cells(board: &SudokuState, index: u8) -> Vec<u8> {

// Get the value of the target cell

let value = board[index as usize];

// Ignore if the target cell is empty (value 0)

if value == 0 {

return Vec::new();

}

// Get related cells

let related_cells = get_related_cells(index);

// Find cells that have the same value as the target cell

related_cells

.into_iter()

.filter(|&index| board[index as usize] == value)

.collect()

}

Note that I am using 0 to represent empty cells.

But if the user ignores the conflicting cells and adds a number to the board, there will be more conflicting cells than the ones related to the target cell. This can be done with another helper function.

Here’s the code, and I took the liberty of adding the docstrings (the /// comments that renders as documentation):

/// Get all the conflictings cells for all filled cells in a Sudoku board

///

/// ## Parameters

///

/// - `current_sudoku: SudokuState` - A reference to the current [`SudokuState`]

///

/// ## Returns

///

/// Returns a `Vec<u8>` representing all cell's indices that are conflicting

/// with the current Sudoku board.

pub fn get_all_conflicting_cells(current_sudoku: &SudokuState) -> Vec<u8> {

let filled: Vec<u8> = current_sudoku

.iter()

.enumerate()

.filter_map(|(idx, &value)| {

if value != 0 {

u8::try_from(idx).ok()

} else {

None // Filter out the item if the value is 0

}

})

.collect();

// Get all conflicting cells for the filled cells

let mut conflicting: Vec<u8> = filled

.iter()

.flat_map(|&v| get_conflicting_cells(current_sudoku, v))

.collect::<Vec<u8>>();

// Retain unique

conflicting.sort_unstable();

conflicting.dedup();

conflicting

}

The trick here is that we are using a flat_map since a naive map would return a nested Vec<Vec<Vec<...>>> of u8s, and we don’t want that. We want a flat Vec<u8> of all conflicting cells. Recursion is always tricky, go ask Alan Turing.

Sudoku App State

As you can see, I used a SudokuState type to represent the state of the game. This is just a type alias for a [u8; 81] array. This is a very simple and efficient way to represent the state of the game.

Here’s the code:

pub type SudokuState = [u8; 81];

The Sudoku app has also an undo button. This is implemented by using a Vec<SudokuState> to store the history of the game. Every time that the user adds a number to the board, the new update state is pushed to the history vector. When the user clicks the undo button, the last state is popped from the history vector and the board is updated.

There’s one additional problem with the undo button. It needs to switch the clicked cell to the one that was clicked before. Yet another simple, but fun, task. First you need to find the index at which two given SudokuState, the current and the last, differ by exactly one item.

Again I’ll add the docstrings since they incorporate some good practices that are worth mentioning:

/// Finds the index at which two given [`SudokuState`]

/// differ by exactly one item.

///

/// This function iterates over both arrays in lockstep and checks for a

/// pair of elements that are not equal.

/// It assumes that there is exactly one such pair and returns its index.

///

/// ## Parameters

///

/// * `previous: SudokuState` - A reference to the first [`SudokuState`] to compare.

/// * `current: SudokuState` - A reference to the second [`SudokuState`] to compare.

///

/// ## Returns

///

/// Returns `Some(usize)` with the index of the differing element if found,

/// otherwise returns `None` if the arrays are identical (which should not

/// happen given the problem constraints).

///

/// ## Panics

///

/// The function will panic if cannot convert any of the Sudoku's board cells

/// indexes from `usize` into a `u8`

///

/// ## Examples

///

/// ```

/// let old_board: SudokuState = [0; 81];

/// let mut new_boad: SudokuState = [0; 81];

/// new_board[42] = 1; // Introduce a change

///

/// let index = find_changed_cell(&old_board, &new_board);

/// assert_eq!(index, Some(42));

/// ```

pub fn find_changed_cell(previous: &SudokuState, current: &SudokuState) -> Option<u8> {

for (index, (&cell1, &cell2)) in previous.iter().zip(current.iter()).enumerate() {

if cell1 != cell2 {

return Some(u8::try_from(index).expect("cannot convert from u8"));

}

}

None // Return None if no change is found (which should not happen in your case)

}

The function find_changed_cell can panic if it cannot convert any of the Sudoku’s board cells indexes from usize into a u8. Hence, we add a ## Panics section to the docstring to inform the user of this possibility. Additionally, we add an ## Examples section to show how to use the function. These are good practices that are worth mentioning and I highly encourage you to use them in your Rust code.

Tests

Another advantage of using Rust is that you can write tests for your code without needing to use a third-party library. It is baked into the language and you can run your tests with cargo test.

Here’s an example of a test for the get_conflicting_cells function:

#[test]

fn test_conflicts_multiple() {

let board = [

1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, // Row 1 with conflict

0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 2 with conflict

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 3

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 4

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 5

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 6

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 7

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 8

1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, // Row 9 with conflict

];

assert_eq!(get_conflicting_cells(&board, 0), vec![8, 10, 72]);

}

And also two tests for the find_changed_cell function:

#[test]

fn test_find_changed_cell_single_difference() {

let old_board: SudokuState = [0; 81];

let mut new_board: SudokuState = [0; 81];

new_board[42] = 1; // Introduce a change

assert_eq!(find_changed_cell(&old_board, &new_board), Some(42));

}

#[test]

fn test_find_changed_cell_no_difference() {

let old_board: SudokuState = [0; 81];

// This should return None since there is no difference

assert_eq!(find_changed_cell(&old_board, &old_board), None);

}

Conclusion

I had a lot of fun building this game. I gave my mother an amazing gift that she’ll treasure forever. Her smartphone has one less spyware now. I deployed a fullstack web app with Rust that is fast, safe and efficient; with the caveat that I didn’t touched any “YavaScript” or complexes build tools.

I hope you enjoyed this post and that you’ll give Rust a try in your next fullstack project.